IBD comprises of two conditions: CD, which is inflammation of one or more parts of the intestines (left), and UC, which is inflammation of the large intestine. — Images: Prof IDA NORMIHA HILMI

Getting the occasional abdominal pain and diarrhoea is common for all of us, but if these symptoms consistently recur, do get yourself checked. You could have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) – a term used to describe two conditions: ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). Like its name suggests, IBD patients have an inflamed gut, and present with pain at the site that is inflamed. UC only affects the colon (large intestine), while CD can affect any or several parts of the digestive tract. Other symptoms may include bloody stools and loss of appetite. As the symptoms are non-specific, patients are normally treated for acute gastroenteritis or misdiagnosed as having irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) – a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterised by abdominal pain and altered bowel habits. “IBD is an autoimmune disorder, where your immune cells attack your bowel. “Our prevalence is low compared to Caucasian or East Asian populations, with less than 10 per 100,000 population; Australia has 125 per 100,000 population. “But it is still a concern, in line with other growing autoimmune disorders,” says Universiti Malaya Medical Centre professor of medicine Dr Ida Normiha Hilmi. The senior consultant gastroenterologist adds: “We don’t know why it happens or what triggers it, although there are many postulations. “These include something in our environment, something we’re doing, changes in our diet that has become more Westernised, one too many courses of antibiotics, stress, smoking, pollution, lack of breastfeeding or a childhood virus. “Or it could be related to the hygiene hypothesis. “Your immune system is meant to be exposed to a lot of bacterial pathogens at an early age, but if the environment has been sterile, then it doesn’t know how to process all these things later on and processes them in an abnormal way. “Once that occurs, it doesn’t switch itself off and there’s no way to reset it.” One of Prof Ida’s colleagues in India has performed mobile colonoscopies in rural areas of that country and found no cases of IBD; however, the locals there had a lot of worms in their guts. “Worms are protective against IBD – they sort of modulate the immune system and there is a symbiotic relationship,” she points out. Late diagnosis IBD a disease that is diagnosed in the young (ages 15 to 40), with a median age of 29; however, there is an increasing trend in the paediatric population.

.An endoscopic image of a normal, healthy colon.>>

It’s not always easy to identify whether the patient has CD or UC, although UC is more common than CD.

“If the doctors don’t know, these patients are placed in the IBDU (IBD unclassified) category,” says Prof Ida, whose youngest IBD patient is 12 years old.

“You’ll be surprised at how many people wait for a year or two before getting treated – the inconsistent pattern of pain often confuses patients and it is normal for them to lose up to 20kg.

“They may go to the general practitioner, get some antibiotics and don’t seek further help.

“Or after several episodes, they finally decide to go to a specialist – maybe all diseases are like that in Malaysia – hence, awareness is very important.

“What they don’t realise is that if the disease is not treated, there is an increased risk of developing colon cancer.”

UC patients can also experience back and knee pain, skin rashes, and liver abnormality – every system can be affected – while CD patients tend to have specific areas affected.

The IBD specialist explains: “The whole gastrointestinal tract is very long, and in a lot of cases, when a CD flare-up happens, it tends to be in the predominant location, i.e. the common location, which is the lower right side (terminal portion of the ileum) – almost the same area as the appendix, which initially raises the suspicion of appendicitis.”

She adds: “There is some old data that shows patterns where if you get IBD once, you will never get it again, but from my experience, it’s rare.

“The disease will recur without treatment.

“It’s not a cure, but with treatment, you can remain in remission.”

Therapy for life

Treatment involves two therapies: induction and maintenance.

.An endoscopic image of a normal, healthy colon.>>

It’s not always easy to identify whether the patient has CD or UC, although UC is more common than CD.

“If the doctors don’t know, these patients are placed in the IBDU (IBD unclassified) category,” says Prof Ida, whose youngest IBD patient is 12 years old.

“You’ll be surprised at how many people wait for a year or two before getting treated – the inconsistent pattern of pain often confuses patients and it is normal for them to lose up to 20kg.

“They may go to the general practitioner, get some antibiotics and don’t seek further help.

“Or after several episodes, they finally decide to go to a specialist – maybe all diseases are like that in Malaysia – hence, awareness is very important.

“What they don’t realise is that if the disease is not treated, there is an increased risk of developing colon cancer.”

UC patients can also experience back and knee pain, skin rashes, and liver abnormality – every system can be affected – while CD patients tend to have specific areas affected.

The IBD specialist explains: “The whole gastrointestinal tract is very long, and in a lot of cases, when a CD flare-up happens, it tends to be in the predominant location, i.e. the common location, which is the lower right side (terminal portion of the ileum) – almost the same area as the appendix, which initially raises the suspicion of appendicitis.”

She adds: “There is some old data that shows patterns where if you get IBD once, you will never get it again, but from my experience, it’s rare.

“The disease will recur without treatment.

“It’s not a cure, but with treatment, you can remain in remission.”

Therapy for life

Treatment involves two therapies: induction and maintenance.

This endoscopic image shows deep longitudinal ulcers in the colon of someone with CD >>

The induction therapy is intended to act fast to provide symptomatic relief, with the mainstay being steroids.

Prof Ida says: “It’s cheap, it works and it works fast, but there are long-term side effects – it thins your bones and causes obesity.”

She notes that the energy boost from the steroids also makes some patients feel better.

However, she adds: “Your adrenal glands that are producing your own steroids are suppressed with chronic steroid use and we have seen patients with Addison’s crisis, where the body is not able to produce steroids any more.

“We never want to give steroids as long-term therapy – we try to stop it within three months.

“If you taper it down and don’t give time for the other immunosuppressive drugs to work, especially slower-acting ones, the symptoms will return, so it’s a balancing act.”

For maintenance, a new group of drugs called biologics work well and have a good safety profile.

The drawback: they’re expensive and range from RM20,000 to RM50,000 annually.

“That’s the difficulty I face with my IBD patients,” Prof Ida laments, “because I’ve to think of costs all the time, especially for the ones without insurance.

“For this reason, I take part in a lot of clinical trials as that allows me to put patients on free drugs.

“Usually, when we get the drugs, we’re already on phase three trials and there are not many concerns as we are not guinea pigs.

“Or we seek funds from charities, non-governmental organisations, etc – that’s the reality.

“The Health Ministry hospitals also have their own free quota, e.g. five patients a year – the rest have to pay.”

For those on clinical trials, the good news is that they can get free drugs for quite a long while.

One of Prof Ida’s patients took part in a landmark IBD study and got free drugs worth about RM48,000 a year for a decade.

Most clinical trials entail a three-month induction and 12-month maintenance timeline.

Every patient usually wants to know when he or she can stop treatment; they think the diarrhoea should resolve with a course of antibiotics.

“The concept of long-term treatment is difficult for them to understand.

“I guess it’s hard when you’re young and have to be on drugs forever, but older people are more accepting,” she says.

“The patient’s function is very much affected as IBD occurs amongst young professionals in high-performing jobs, hence I try to normalise their lives as much as possible.”

For those who don’t succeed with medical therapy, they have to undergo surgery to resect their bowel.

In the past, the figure was 70%, but with better medications these days, the figure has gone down to about 20-30%.

What about foods?

“Before, we didn’t really know what to tell our patients in terms of diet, except to have a low-fibre diet, because when your colon is inflamed, the bowel is narrowed, and if you take too much fibre, it may block your passage.

“Now, we’re looking at anti-inflammatory diets, although we’re still far from anything concrete.

“My paediatric colleagues practise entero-nutrition (delivered into the digestive system as a liquid) for six weeks, but maintenance is difficult as you can’t be on liquid nutrition for the rest of your life,” says Prof Ida.

She suggests, however, that patients try to reduce pro-inflammatory foods, such as those with high fat content.

When it comes to herbs, she says turmeric might help, but the dose has to be right.

“If you have a bad case of UC, you still need biologics as turmeric is not going to save you.

“Everyone is also asking about probiotics.

“Not all probiotics in the market are medical grade, but if my patients want to take it and it makes them feel better, I don’t stop them.

“Our gut consists of trillions of gut microorganisms and taking a tablet or two a day is not going to touch the diversity or repopulate the microbiome.

ALSO READ: Think you know all about probiotics? Then take this quiz

“When the colon is inflamed, the pathogenesis is very complex – we think something is happening at the gut level, maybe a breach of some bacteria into your gut wall – and sometimes, the immune system goes awry.

“But there is also something else that is causing this and we can’t quite pinpoint it.”

The inheritance pattern of this condition is unclear, although some studies show that having a family member with IBD increases the risk of developing the condition.

However, Prof Ida has two sets of identical twin patients.

In one set, only one twin has UC, and in the other, only one twin has CD.

They grew up in the same environment, ate the same foods, and have the same genes, which indicates that some other factor is playing a role in the disease.

Our gut microbiome is developed by the time we’re one-year-old and that’s the one we keep, with minor alterations over the years.

She says: “When you go to another country, it may change a bit, but when you go back to your own country, it generally goes back to your original gut microbiome.”

ALSO READ: The good gut bacteria in our microbiome might be disappearing

Storing and transferring poo

This endoscopic image shows deep longitudinal ulcers in the colon of someone with CD >>

The induction therapy is intended to act fast to provide symptomatic relief, with the mainstay being steroids.

Prof Ida says: “It’s cheap, it works and it works fast, but there are long-term side effects – it thins your bones and causes obesity.”

She notes that the energy boost from the steroids also makes some patients feel better.

However, she adds: “Your adrenal glands that are producing your own steroids are suppressed with chronic steroid use and we have seen patients with Addison’s crisis, where the body is not able to produce steroids any more.

“We never want to give steroids as long-term therapy – we try to stop it within three months.

“If you taper it down and don’t give time for the other immunosuppressive drugs to work, especially slower-acting ones, the symptoms will return, so it’s a balancing act.”

For maintenance, a new group of drugs called biologics work well and have a good safety profile.

The drawback: they’re expensive and range from RM20,000 to RM50,000 annually.

“That’s the difficulty I face with my IBD patients,” Prof Ida laments, “because I’ve to think of costs all the time, especially for the ones without insurance.

“For this reason, I take part in a lot of clinical trials as that allows me to put patients on free drugs.

“Usually, when we get the drugs, we’re already on phase three trials and there are not many concerns as we are not guinea pigs.

“Or we seek funds from charities, non-governmental organisations, etc – that’s the reality.

“The Health Ministry hospitals also have their own free quota, e.g. five patients a year – the rest have to pay.”

For those on clinical trials, the good news is that they can get free drugs for quite a long while.

One of Prof Ida’s patients took part in a landmark IBD study and got free drugs worth about RM48,000 a year for a decade.

Most clinical trials entail a three-month induction and 12-month maintenance timeline.

Every patient usually wants to know when he or she can stop treatment; they think the diarrhoea should resolve with a course of antibiotics.

“The concept of long-term treatment is difficult for them to understand.

“I guess it’s hard when you’re young and have to be on drugs forever, but older people are more accepting,” she says.

“The patient’s function is very much affected as IBD occurs amongst young professionals in high-performing jobs, hence I try to normalise their lives as much as possible.”

For those who don’t succeed with medical therapy, they have to undergo surgery to resect their bowel.

In the past, the figure was 70%, but with better medications these days, the figure has gone down to about 20-30%.

What about foods?

“Before, we didn’t really know what to tell our patients in terms of diet, except to have a low-fibre diet, because when your colon is inflamed, the bowel is narrowed, and if you take too much fibre, it may block your passage.

“Now, we’re looking at anti-inflammatory diets, although we’re still far from anything concrete.

“My paediatric colleagues practise entero-nutrition (delivered into the digestive system as a liquid) for six weeks, but maintenance is difficult as you can’t be on liquid nutrition for the rest of your life,” says Prof Ida.

She suggests, however, that patients try to reduce pro-inflammatory foods, such as those with high fat content.

When it comes to herbs, she says turmeric might help, but the dose has to be right.

“If you have a bad case of UC, you still need biologics as turmeric is not going to save you.

“Everyone is also asking about probiotics.

“Not all probiotics in the market are medical grade, but if my patients want to take it and it makes them feel better, I don’t stop them.

“Our gut consists of trillions of gut microorganisms and taking a tablet or two a day is not going to touch the diversity or repopulate the microbiome.

ALSO READ: Think you know all about probiotics? Then take this quiz

“When the colon is inflamed, the pathogenesis is very complex – we think something is happening at the gut level, maybe a breach of some bacteria into your gut wall – and sometimes, the immune system goes awry.

“But there is also something else that is causing this and we can’t quite pinpoint it.”

The inheritance pattern of this condition is unclear, although some studies show that having a family member with IBD increases the risk of developing the condition.

However, Prof Ida has two sets of identical twin patients.

In one set, only one twin has UC, and in the other, only one twin has CD.

They grew up in the same environment, ate the same foods, and have the same genes, which indicates that some other factor is playing a role in the disease.

Our gut microbiome is developed by the time we’re one-year-old and that’s the one we keep, with minor alterations over the years.

She says: “When you go to another country, it may change a bit, but when you go back to your own country, it generally goes back to your original gut microbiome.”

ALSO READ: The good gut bacteria in our microbiome might be disappearing

Storing and transferring poo

Prof Ida concludes: “Patients need to understand that disease control is important, and if all therapies fail, surgery, despite its drawbacks, is the only option.” - By Revathi Murugappan

By

By

The line-up of three taikonauts for Shenzhou-15 manned spaceflight mission, Zhang Lu, Fei Junlong, and Deng Qingming (from left to right). Photo: VCG

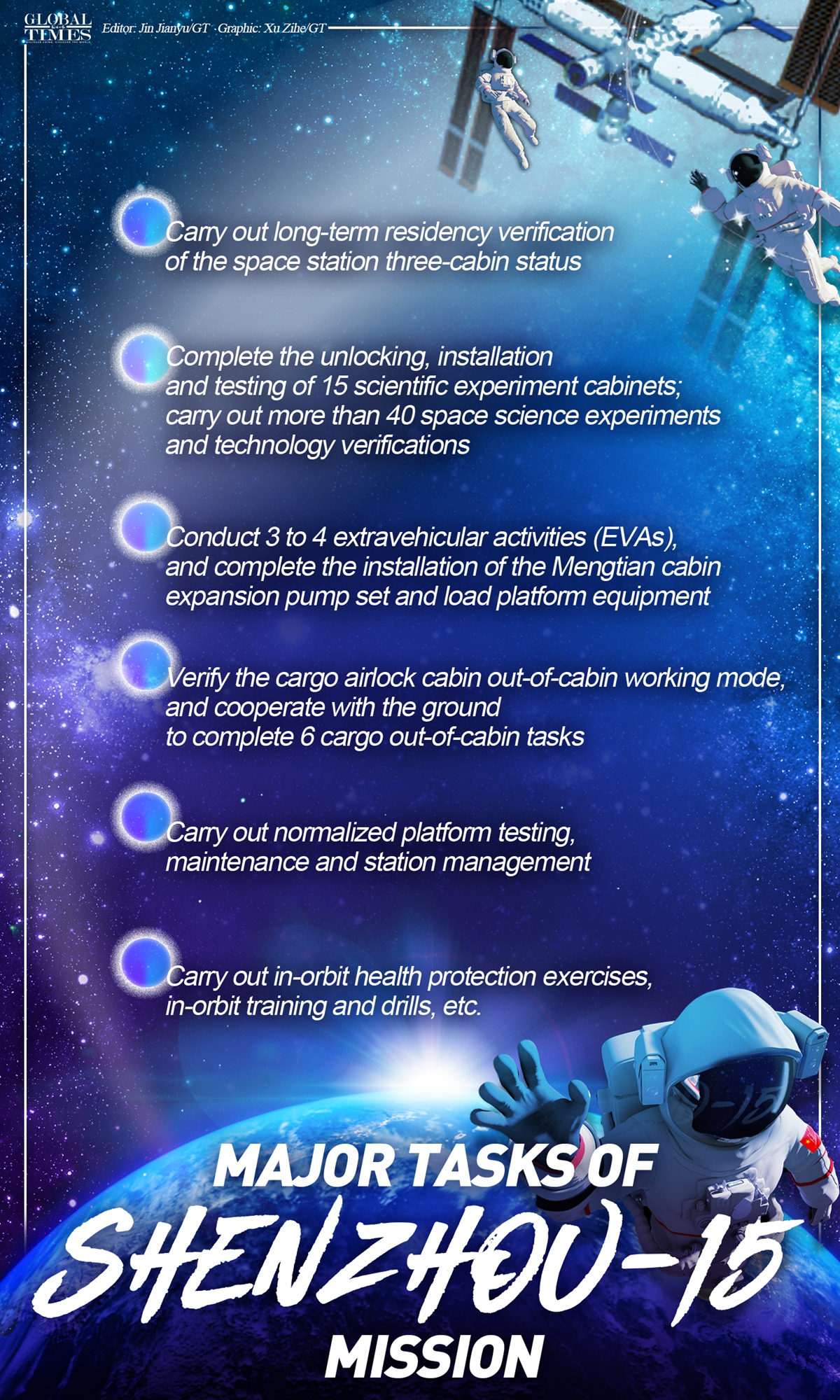

China on Monday unveiled the line-up of three taikonauts for Shenzhou-15 manned spaceflight mission that is set to be launched on Tuesday night. The trio led by mission commander Fei Junlong with two space newcomers Deng Qingming and Zhang Lu are going to conduct a direct handover in orbit with the Shenzhou-14 crew at the China Space Station in construction, which shall mark a first in China's aerospace history.

The upcoming Shenzhou-15 crewed spaceflight mission is not only the anchor-leg launch mission at the China Space Station construction stage, but also is the first one to embark on the next operational stage, Fei, the 57-year-old veteran taikonaut who visited the space as the mission commander in the China's Shenzhou-6 mission in 2005, remarked at a press conference on Monday at the Jiuquan Satellite Space Launch Center in Northwest China's Gansu Province.

The crew will carry out more experiments in orbit, operate, maintain and repair relevant equipment and above all execute even more challenging extravehicular activities, or known as spacewalks, with more complicated paths to take on, Fei said on Monday.

The Shenzhou-15 crew has undergone great amount of specific training, which made them very confident to deliver all the set goals and to successfully complete their space run, Fei said.

Deng Qingming, 56, is among the first batch of taikonauts trained in China that includes the country's first astronaut Yang Liwei and also his mission commander Fei in the Shenzhou-15 mission. He has served as a backup for nearly 25 years, in missions such as the Shenzhou-9 and 10, but never got the chance to fly. This will be his first time ever in space.

Zhang Lu, 46, also a new face, was selected in the second batch of taikonauts trained in China in 2010.

Mission insiders told the Global Times on Monday that the two crews of six taikonauts will carry out the space station handover in a face-to-face manner for the first time in the country's manned space history and that is not only of symbolic significance but also carries great practical values to the overall development of the country's first permanent space outpost.

Sources with China's astronaut training system, told the Global Times on Monday that such feat would enable the predecessor Shenzhou-14 to introduce and share what their work and life would be like inside the space station with the new Shenzhou-15 crew directly, boosting the continuity and efficiency of the handover.

It would also help save the resources to set the space station combo from occupied state to unoccupied one and then back again. And the handover will be more target-oriented, especially for those ongoing experiments and space station maintenance work, the sources said.

Having six taikonauts simultaneously onboard the China Space Station in construction, would also verify its performance under the full load condition, which would lay groundwork for future tasks where more payload technicians are needed for more complicated experiments, Song Zhongping, a space watcher and TV commentator, told the Global Times.

By plan, the handover will last for a week or so, and after that, Shenzhou-14 crew will return to the Dongfeng landing site on Earth.

As the temperature drops to somewhere near minus 20 C in Jiuquan around this time of the year, the launch of Shenzhou-15, which is via a Long March-2F rocket from the Jiuquan center, also faces a special challenge of extremely low temperature.

According to the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (CALT), the developer of the Long March-2F rocket, Shenzhou spacecraft had only been launched twice in unscrewed condition during the Shenzhou-1 and 4 missions in late November. Shenzhou-15 would be first one to be carried out with taikonauts onboard in the cold weather.

However, the CALT explained that they have taken such unique challenge into consideration. They have also confirmed the two sets of the temperature system inside the rocket's nose cone, to make sure that the temperature of the propellant of the return and propelling module meets the launch condition.

The line-up of three taikonauts for Shenzhou-15 manned spaceflight mission, Zhang Lu, Fei Junlong, and Deng Qingming (from left to right). Photo: VCG

China on Monday unveiled the line-up of three taikonauts for Shenzhou-15 manned spaceflight mission that is set to be launched on Tuesday night. The trio led by mission commander Fei Junlong with two space newcomers Deng Qingming and Zhang Lu are going to conduct a direct handover in orbit with the Shenzhou-14 crew at the China Space Station in construction, which shall mark a first in China's aerospace history.

The upcoming Shenzhou-15 crewed spaceflight mission is not only the anchor-leg launch mission at the China Space Station construction stage, but also is the first one to embark on the next operational stage, Fei, the 57-year-old veteran taikonaut who visited the space as the mission commander in the China's Shenzhou-6 mission in 2005, remarked at a press conference on Monday at the Jiuquan Satellite Space Launch Center in Northwest China's Gansu Province.

The crew will carry out more experiments in orbit, operate, maintain and repair relevant equipment and above all execute even more challenging extravehicular activities, or known as spacewalks, with more complicated paths to take on, Fei said on Monday.

The Shenzhou-15 crew has undergone great amount of specific training, which made them very confident to deliver all the set goals and to successfully complete their space run, Fei said.

Deng Qingming, 56, is among the first batch of taikonauts trained in China that includes the country's first astronaut Yang Liwei and also his mission commander Fei in the Shenzhou-15 mission. He has served as a backup for nearly 25 years, in missions such as the Shenzhou-9 and 10, but never got the chance to fly. This will be his first time ever in space.

Zhang Lu, 46, also a new face, was selected in the second batch of taikonauts trained in China in 2010.

Mission insiders told the Global Times on Monday that the two crews of six taikonauts will carry out the space station handover in a face-to-face manner for the first time in the country's manned space history and that is not only of symbolic significance but also carries great practical values to the overall development of the country's first permanent space outpost.

Sources with China's astronaut training system, told the Global Times on Monday that such feat would enable the predecessor Shenzhou-14 to introduce and share what their work and life would be like inside the space station with the new Shenzhou-15 crew directly, boosting the continuity and efficiency of the handover.

It would also help save the resources to set the space station combo from occupied state to unoccupied one and then back again. And the handover will be more target-oriented, especially for those ongoing experiments and space station maintenance work, the sources said.

Having six taikonauts simultaneously onboard the China Space Station in construction, would also verify its performance under the full load condition, which would lay groundwork for future tasks where more payload technicians are needed for more complicated experiments, Song Zhongping, a space watcher and TV commentator, told the Global Times.

By plan, the handover will last for a week or so, and after that, Shenzhou-14 crew will return to the Dongfeng landing site on Earth.

As the temperature drops to somewhere near minus 20 C in Jiuquan around this time of the year, the launch of Shenzhou-15, which is via a Long March-2F rocket from the Jiuquan center, also faces a special challenge of extremely low temperature.

According to the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (CALT), the developer of the Long March-2F rocket, Shenzhou spacecraft had only been launched twice in unscrewed condition during the Shenzhou-1 and 4 missions in late November. Shenzhou-15 would be first one to be carried out with taikonauts onboard in the cold weather.

However, the CALT explained that they have taken such unique challenge into consideration. They have also confirmed the two sets of the temperature system inside the rocket's nose cone, to make sure that the temperature of the propellant of the return and propelling module meets the launch condition.